Working to Understand Anger is Peace Work

How to Befriend Anger

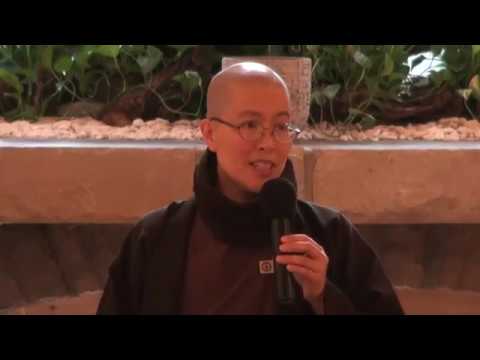

We’re in the Great Meditation hall at Magnolia Grove Monastery. On the third day of US tour retreat entitled "Peace in oneself, peace in the world"

I hope everyone has had a chance to settle in and become acclimated to the changing climate. It’s usually nice to be at a monastery for at least three or four days because it takes time for the body and the mind to shift gears from the speed and pace outside. Sometimes, if we don’t allow our body and mind to settle, we continue to run even in the monastery.

We were very fortunate to bathe in a very beautiful bath of dharma by Sister Chan Duc. In her talk, we learned about pleasant, neutral, unpleasant, and mixed feelings. I’m very aware right now that in this big hall, there’s not a single mosquito biting me. That neutral feeling is actually a very pleasant feeling.

We can touch the practices of mindfulness in very concrete ways. In in our daily life, moment to moment, if we look with the eyes of a practitioner, there’s always a chance for us to explore our mind and explore the minds of others in order to come to a deeper level of understanding.

I’d like to go further in the practice of peace. We learned that peace comes from awareness of our pleasant feelings and our neutral feelings. Just from that awareness, happiness can spring forth.

We also know that we just don’t experience pleasant and neutral feelings. We are a whole spectrum. We have quite unpleasant feelings sometimes. The practice of peace, being peace within oneself, isn’t just to be with our pleasant and neutral feelings but learning to engage with, relate to, and transform those unpleasant feelings as well. The practice of peace is the spirit of peace with which we relate to those icky mosquitoes, those pesky conversations, those irritations.

It also plays out in the social sphere. We are very aware that what we do here is not just for our small insular self, or even just for our family. It has a great impact on society. Our capacity to take care of those uncomfortable feelings gives us strength to face, confront, and help to transform those things that are much larger and much more troublesome in society.

Peaceful Confrontation That Has a Positive EffectPeaceful confrontation is an actuality. A possibility. But only if we put our energy of practice into it.

I remember a particular incident that has always stayed with me. A number of years ago, we visited our neighbors in Canada. We had a lazy day, so we took a walk out on the town, it was a number of brothers and sisters together. During the walk, there was a gentleman who started to follow us. He engaged in speech that was inquisitive--not necessarily negative--but certainly a little provocative. He started to follow and try to engage the sisters in the group. This went along for maybe half a block or a block. But because the sisters were not reacting, the gentleman’s engagement started escalating. It was touching something in him, and he starting getting a little pushy and aggressive.

When he realized what was happening, one of the monks in our group very quickly, but very kindly--the energy was confrontational but peaceful, not angry at all--turned to the man, held out his hand as if to stop the gentleman, and said, “Whoa, whoa. We’re just having a peaceful walk here. I’m sure you can understand.” While the sisters and brothers continued to walk, our brother engaged the gentleman in conversation about who we were, what we were doing, and why we were wearing brown.

That image of that brother taking that action very peacefully, stayed with me. And for me is an example that if we are from a place of peace, a place of clarity, we can engage in action that has a positive effect. Instead of escalating the matter, it is a way for both parties to move forward.

Anger Work is Peace Work. Peace Work is Anger WorkThis talk is dedicated to one of our favorite strong emotions. Out of fear, despair, and anger, I decided to focus on anger.

We know that working on anger is not just a “management”. We hear that sometimes, “anger management.” I want to emphasize that working to understand our anger is peace work. Peace work, is anger work. Anger work, is peace work. It is important that we engage in this mud because we should give ourselves permission to be fully human. We are fallible. We make mistakes, and we dip into negative afflictions. We need to acknowledge that understanding our anger is a practice of loving kindness for ourselves and all of humanity, and when we can begin to acknowledge the seed of anger within us, we can begin to have peace with parts of ourselves that are uncomfortable.

How many of us here have anger issues? Maybe that is harsh to say, so how many of us sometimes have challenges with anger? How many of us knows someone who has issues with anger?

Honestly, most of us at this point should be able to relate. Because as we learn from Buddhist psychology, each one of us has all of these positive and negative seeds, meaning wholesome and unwholesome qualities. It’s just a matter of fact to say, “Yes, I have anger in me. Yes, my loved ones have anger in them. And yes, sometimes I water that anger in them quite a lot.” Recognizing anger is a loving approach to this seed.

Acknowledge Anger in Order to Become More WholeFirst of all, we acknowledge our anger in order to become more whole. We also need to practice with our anger because if we leave this particular seed untended, it can have quite harmful effects. We already see how in our relationships, when we have conflicts and don’t take care of our anger or acknowledge the other person’s anger, it festers.

We know anger is a force to be reckoned with, but as an emotion, in Buddhism, we know its rightful place in our lives. Maybe it’s taking up quite a lot of space in our heart and mind right now, but the teachings point to a drawer that we can put this emotion. It is an emotion. Our teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, would say, “It is just an emotion.” It is not to negate its power but to help us have a working, loving relationship with anger.

A Gateway into a Deeper Level of UnderstandingFor me, I respect anger greatly, first of all, because I can see how harmful it is in me. It wreaks havoc in my peace of mind. Sometimes when I’m bit by anger, it takes me quite a long time to come back to a place of stillness, clarity, and loving kindness. And I can see it in my relationships with others, when I touch someone else’s anger, I have to deal with the karma of that. And who wants that? It’s something that we respect because it has the power to very negatively affect the environment.

We also respect our own emotions and other people’s emotions because it is a gateway into a deeper level of understanding. What is at the heart of what we value? What is it that we hold dear? What we are afraid of? Anger is that gate that allows us to see ourselves more clearly, sometimes quite suddenly.

How Do You Define Anger?Let’s take a step back and look at anger in an academic way:

To define it, anger is an intense displeasure aimed toward the thing, person, or situation that we perceive as hurting, harming, offending, or annoying us. The question before us then, is what is anger challenging?

Have you ever had a callous? On your foot or your hand? We know that the body has a way to deal with pain and sensitivities. For example, I play guitar. The nerves under my fingers are quite sensitive, so when I play guitar, a callous forms in order to protect that area of sensitivity.

I’d like to invite you to reflect on anger as a combination of hardness or harshness--the callous-- and the underlying sensitivity. What sensitivity lies underneath our anger? That is the question.

I remember, a friend of mine in college almost overdosed. At the time, I didn’t know that she was trying to block out pain. Instead, I thought that she was trying to commit suicide, and I didn’t understanding why. When I heard that she overdosed, it touched a strong fear and a strong anger. I confronted her and asked, “How could you do that?! What were you thinking?” Later, I learned that she wasn’t trying to harm or hurt herself. She was just trying to block out her pain with the pills and that was the only way she knew how. In that situation, both she and I touched desperation and fear. Mine turned to anger, and hers turned to trying to escape.

There’s a relationship between fear and anger sometimes. How many of us are parents? Do you ever get angry at your children because they did something that scared the heeby jeebies out of you? That fear can quickly turn into anger. This is a reaction that we need to look carefully at in order to get at the roots. Fear is one side, one kind of sensitivity. Fear is a feeling of being afraid, when something in us that was secure is no longer secure.

Underneath the harshness, the prickliness of anger, is also our sense of self. Our manas, which are what we define as who we are and what belongs to us: I, me, mine. When our sense of self is threatened, that can give rise to anger. “How dare you cut in front of me while I’m driving?! This lane belongs to me!” Road rage is a strange phenomenon, but when you look at it in the light of a sense of self, it becomes a little bit more understandable. “How dare you take that from me?! That belongs to me! How dare you challenge my worldview?! My view.” So it all has something to do with our sense of self, our pride, or what we feel entitled to. Nevermind whether we actually are entitled to it or not.

Anger can be seen as a habit energy manifesting in reaction to something. Our habit energy can come in many ways. A physical habit energy of anger could be, for example, when we stub our toe. Right away, we yell at the table. That kind of anger doesn’t make sense, but it is a habit. An emotional habit energy of anger could fear from a place of insecurity. For example, that feeling you get when our child comes home late at 4 in the morning and you don’t know where they’ve been. That sense of fear for your child immediately turns into anger: “How could you make me feel that way?!” The mental habit energy of anger comes from a sense of self. Our sense of entitlement. I have a way of thinking about myself as an elder sister, a younger sister, as a woman, or an equal. If this is challenged by someone’s actions or words, this can touch some anger. It is a blockage. It is a challenge. Something we perceive that will injure this ego of ours. “You think you’re cool? You’re not that cool.”

To hear more of Sister True Vow’s sharing on anger, click on this video: 2017 US Tour: Magnolia Grove: Second talk, Sr. True Vow - https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1439&v=ikWHkteVz94

( Press Release Image: https://photos.webwire.com/prmedia/7/216256/216256-1.jpg )

WebWireID216256

This news content was configured by WebWire editorial staff. Linking is permitted.

News Release Distribution and Press Release Distribution Services Provided by WebWire.